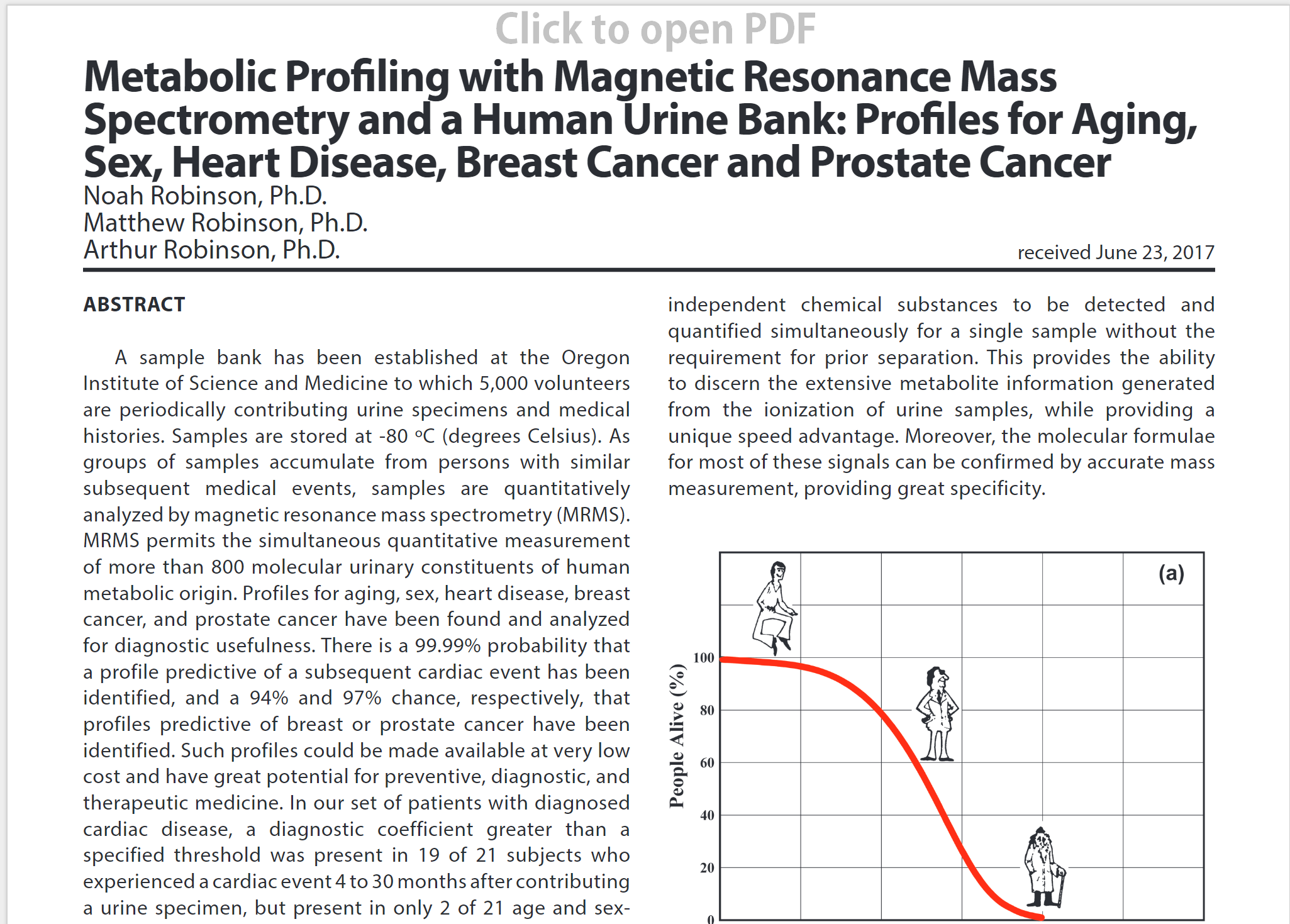

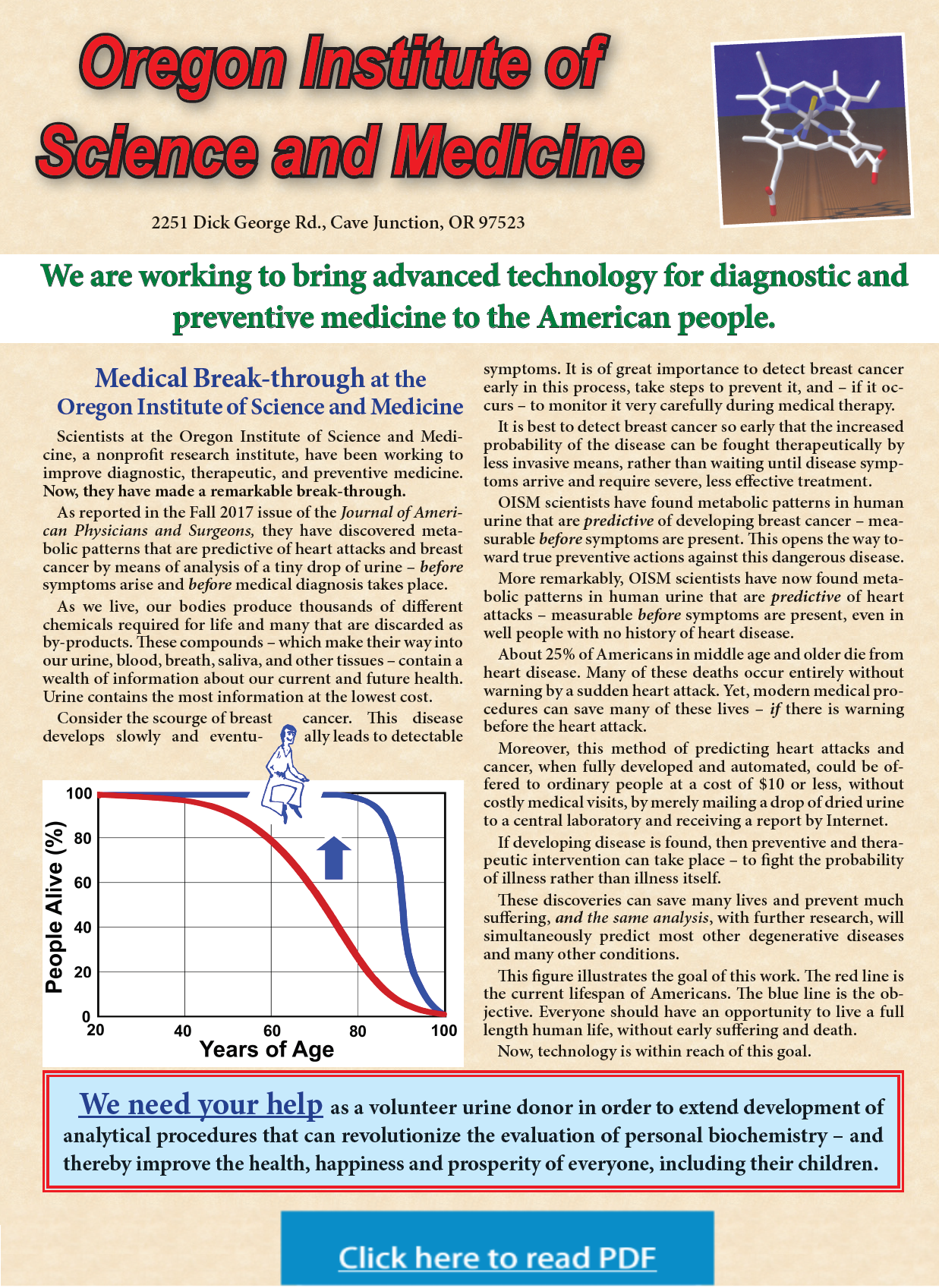

About 27 percent of Americans die of heart disease, and the first sign may be sudden death. A revolutionary study in the fall issue of the Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons shows that about 90 percent of patients who experienced a cardiac event had a specific pattern present in a urine specimen contributed to a sample bank as long as 30 months before the diagnosis of heart disease. Other identifiable patterns were also present in patients later found to have breast cancer or prostate cancer.

The analytical technique uses magnetic resonance mass spectrometry, which determines the ratios of more than 800 substances present in a tiny drop of urine.

The concept of metabolic profiling, focused on easily and cheaply measured substances found in body fluids, was pioneered by Arthur Robinson and his colleagues at the University of California at San Diego, Stanford University, and the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine in the 1970s. Patterns were found to exist for many conditions, including multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, and Huntington disease. Progress was limited by technology and the lack of longitudinal samples.

The Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine has developed a urine sample bank with cryogenically preserved specimens from 5,000 volunteers, who periodically send samples and medical information. If enough subjects develop a condition of interest, these samples can be analyzed. Once a library of profiles is compiled, information from individual patients’ serial samples could be used to monitor their health quantitatively and assess the effect of interventions on the probability of developing a full-blown disease.

Unlike other methods that focus on expensive measurements of a few substances characteristic of a specific disease, this research aims to develop a frequently repeatable $5 test that measures all common metabolic products whose relative concentrations are influenced by disease processes. As this bank is expanded and matures, it will make possible the discovery of profiles for less prevalent diseases. One single test that everyone could afford has the potential to determine the probability of most diseases.

Currently, this is a research technique only. Federal law prohibits use of the information to diagnose or treat patients.

To participate, print and send in this form.

The Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine is a non-profit research institute established in 1980 to conduct basic and applied research in subjects immediately applicable to increasing the quality, quantity, and length of human life. Research in the Institute's laboratories includes work in protein biochemistry, diagnostic medicine, nutrition, preventive medicine, and aging. The Institute also carries out work on the improvement of basic education and emergency preparedness.

The Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine is a non-profit research institute established in 1980 to conduct basic and applied research in subjects immediately applicable to increasing the quality, quantity, and length of human life. Research in the Institute's laboratories includes work in protein biochemistry, diagnostic medicine, nutrition, preventive medicine, and aging. The Institute also carries out work on the improvement of basic education and emergency preparedness.

|

Revolutionizing Diagnostic Medicine Click here to learn how you can participate. |